Olivier Goethals

This interview was conducted during the Paraply Summer School in Copenhagen, August 2025.

During the Paraply Summer School, I sat by the water with Olivier Goethals to talk about his practice and approach. In the background, participants were sawing and drilling, and throughout the interview, we observed their process and engagement with the material.

Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart, Berlin. Spatial intervention / exhibition design for the groupshow 'Nationalgalerie: A Collection for the 21st Century'. © Michiel De Cleene

#1 Can you describe your practice in a few sentences?

My practice is rooted in architecture and urbanism. I worked for about ten years in architectural offices and as a freelance architect, but early on my interest expanded towards the art scene. Together with friends, I run two off-spaces in Ghent, where we curate exhibitions and build installations ourselves.

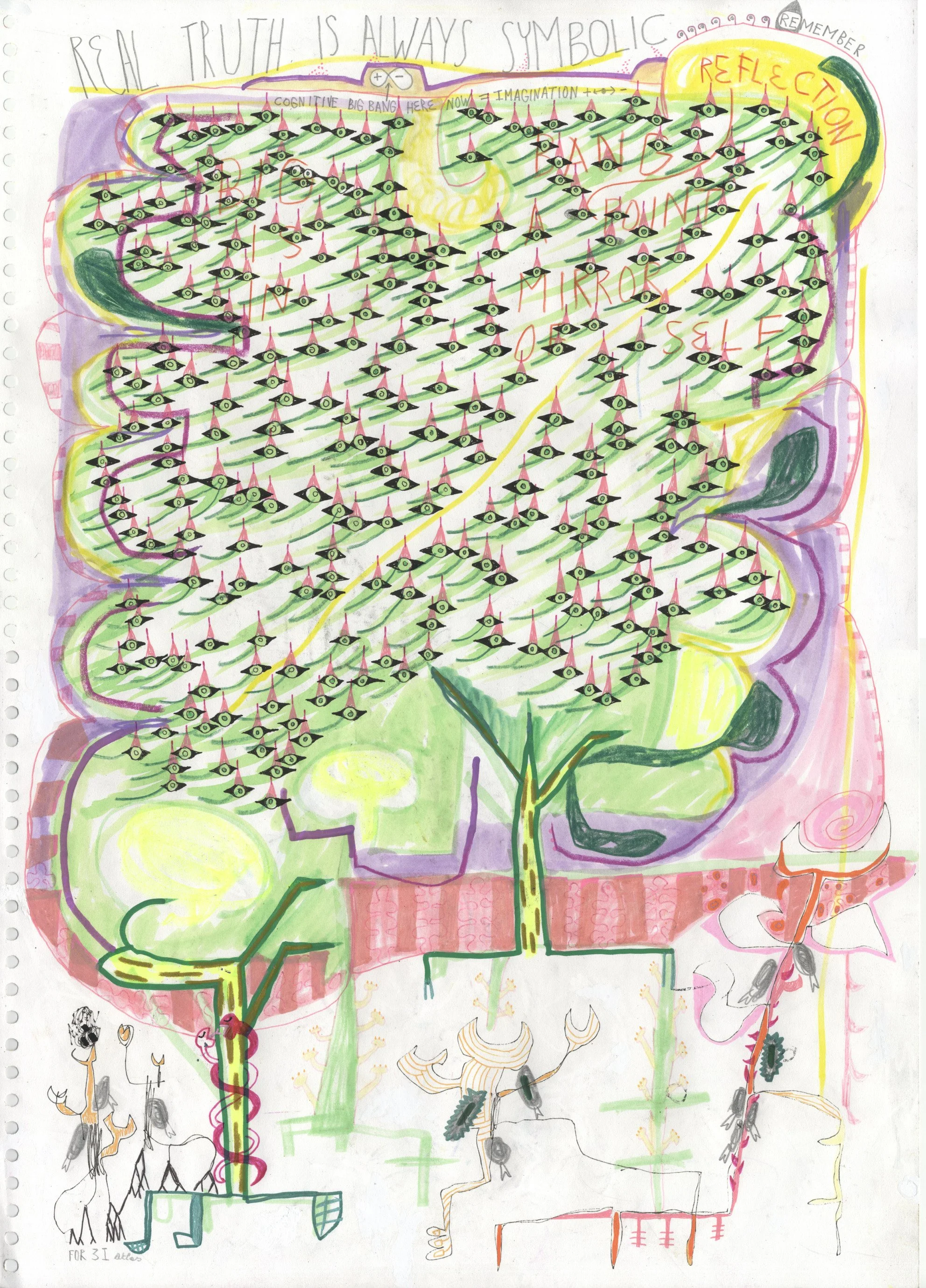

In my personal practice, I mainly work in scenography for museums and galleries, including projects for institutions such as Palais de Tokyo and Hamburger Bahnhof. Parallel to this, I paint and draw, occasionally exhibiting this work. Architecture, scenography, drawing and curating are closely intertwined in my practice, with strong connections between spatial design and the content of my artworks.

#2 How would you describe the formal language of your paintings and drawings—are they more spatial and abstract, or rooted in line and gesture?

The paintings engage with the metaphysics of space: what space is, how it relates to time, and the tension between what we can perceive and what remains beyond our senses. I read a lot of philosophy, which strongly informs the way I think about space and how this thinking enters my work.

I have a somewhat idiosyncratic definition of space: for me, it is the experience of relationships between things and our perception of them. To create a meaningful space means to intensify these relationships. When the number and density of these relationships increase, a sense of meaning emerges; often perceived as a form of well-being.

Book10 Gospel, 2022-2025

#3 What inspires you or drives your approach to architecture?

What inspires me is playing. I really like to work intuitively. For me, intuition is the experience of truth in between thinking. When you are creative, you do not think rationally; you can be amazed by the things you do yourself. It is a playful state.

Being playful and being inspired feel like the same thing to me: enthusiasm, inspiration, play. The word inspiration contains spiritus, and in Dutch begeesterd carries the idea of a ghost being present. I truly believe you have to be playful to make work. When you are playful, you do not care about the result; you care about the doing, about presence. You are not trying to become a famous artist; you simply enjoy putting paint on a surface, and as a consequence, a good artwork emerges.

If you are too busy with the end result, you are no longer in the moment, and what you make loses that playfulness at its core.

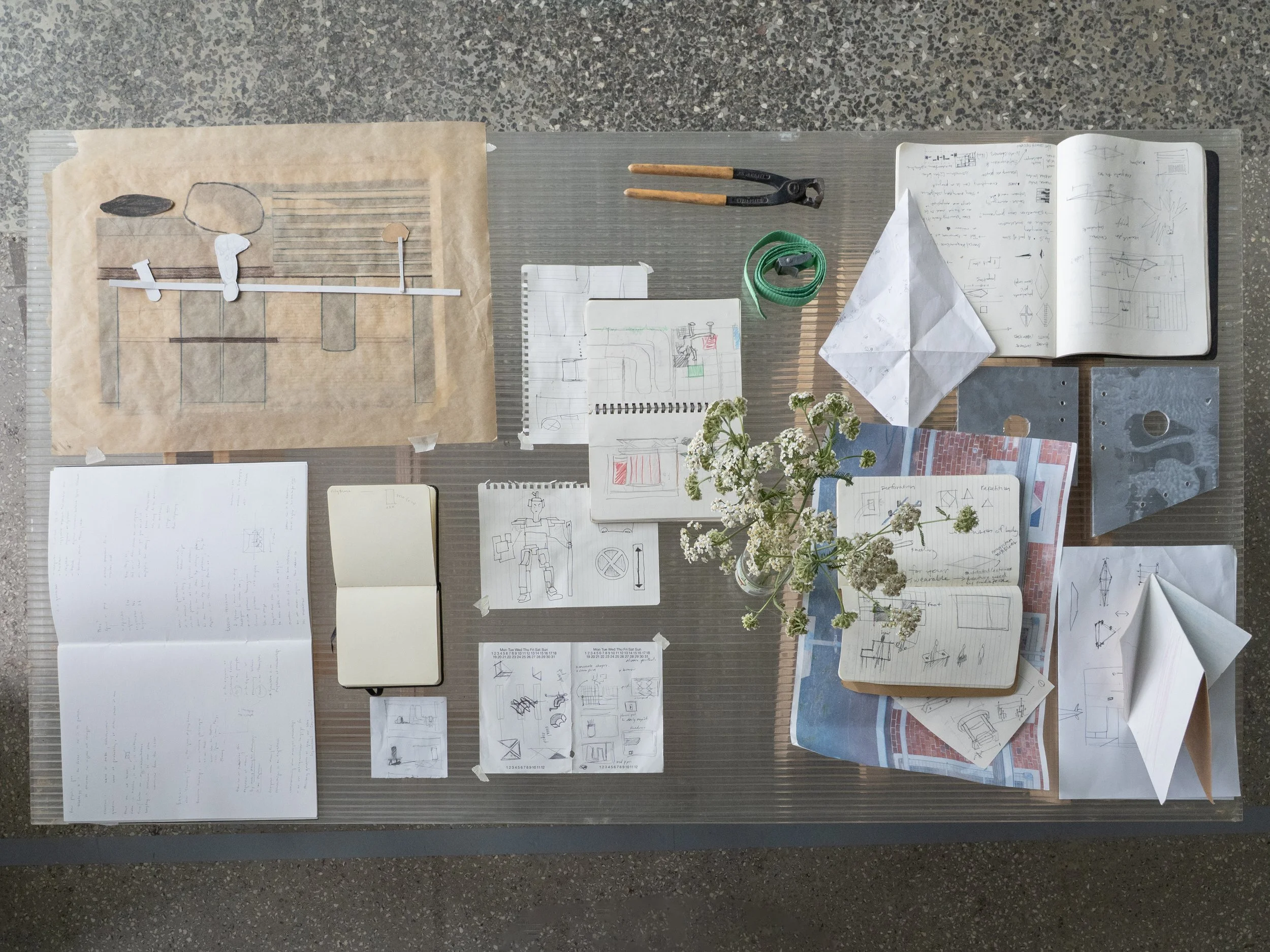

Workshop by Olivier Goethals, Team: Marion De Bie, Lukas Raabe, Vinzent Hadschieff, Photos: © Samuel Causse

#4 Can you describe your brief for the Paraply Summer School?

When we received the brief as workshop leaders, it came as an abstract text dealing with the everyday and the notion of load, what load can mean within building practice. At that point, we also did not know which materials would be available. I proposed starting from an image.

Each student group was asked to explore the city of Copenhagen and find a place with a layered history, sites where different layers of design, age, and traces of use are visible. They would take a photograph of this place and then insert themselves into the image together with an object they had made in order to rebalance the composition. Through this addition, a new composition emerges from the original photograph.

The objects were to be informed by details, rhythms, or harmonics found in the image, sampled and translated into elements attached to the body. The result is an architectural wearable object. The students then had to pose within the chosen context. The photograph functions like the background of a fashion shoot, where the setting is consciously selected and the object only reveals its meaning when carried.

The final outcome consists of the initial photograph, a second image taken at the end, and an object that is not stable on its own but must be worn to be understood.

Workshop by Olivier Goethals, Photo: © Samuel Causse

#5 Why was it important for you to include the body in the task, rather than treating the object as something autonomous?

Because it gives the students something to work around. If they build an object that can simply stand on its own, the body remains absent. By including themselves, they have to feel the weight of the object, account for its load, and think about how it is handled and carried. The act of carrying becomes part of the work and is expressed in the object itself.

This can take very concrete forms: handles, openings for fingers, or elements that require the body to become part of the composition. In this way, the object gains a more playful and interactive meaning, because it only fully exists through use and engagement.

#6 What do you hope students take away from the workshop?

I value the social aspect most: working together, and having to choose within their groups of two or three a person to focus on. That already introduces an important social dynamic. Beyond that, it’s about the process of building, but also the playfulness of the exercise. It doesn’t have to be serious, but it requires sincere play - an honest engagement.

Students create something sincere without stress, exploring materials, collaging, assembling, and testing the limits of what can be carried. Every choice is made in the moment. The work grows and evolves constantly while it is being built, shifting with each new decision.

Workshop by Olivier Goethals, Team: Philipp Kitzberger, Mike Sullivan, Gabe Higgins, Photos: © Samuel Causse

#7 What do you personally take away from the workshop?

It’s a really enjoyable week for me. I’m happy to meet new people, have nice conversations, enjoy good food, and the beautiful weather. That’s not the core of my expertise, of course, but it’s part of the experience. Beyond that, I genuinely enjoy seeing participants discover new skills: simple things like how to hold a drill, how to saw, or how to work with materials they’ve never handled before. I like helping them, sharing the little expertise I have in building, and watching them accomplish things they didn’t think they could. These workshops give me a real sense of being useful and of contributing something meaningful.

#8 From your perspective, what ideas or questions do you think are most urgent for the next generation of architects?

Oh, that is a very broad question and a tricky one. Of course, there is all the talk about sustainability, and while that narrative is true, I do not think the responsibility for real change lies solely with architecture. It is primarily a political responsibility. There are alternative ways of producing energy that have existed since the end of the fifties. Our culture has consciously chosen to rely on oil to maintain the existing power structures.

The sustainability of the future depends on those in power being willing to give up part of their control, and they do not want to. I do not believe that architecture alone can save the world. What architects can do, however, is approach our environment critically and aim to make it beautiful. This means creating an urban fabric with thoughtful composition, plenty of trees, diverse uses, and spaces that express freedom.

Making beautiful spaces matters because people who live in beautiful environments tend to be healthier, happier, and more compassionate toward each other. I do not think we should make everything as sustainable and bland as possible. Instead, we should strive for beauty in everything we build, while asking politicians and those in power to create new energy systems. If energy were cheap, abundant, and non-oil based, we could build sustainably without extreme measures like over-insulation. That is my honest opinion.

#9 How has the city of Copenhagen inspired you?

Well, the fact that most of them had never been here made it especially nice. I myself was only here for the first time this past January, so this is only the second time I have visited this year. It is a lovely city with a very well-structured urban fabric and plenty of well-organized public spaces. It is generous in scale. Although it is somewhat gentrified, it still has character and offers spaces where people can simply hang out with friends without the need to buy anything. It is not completely privatized, so it remains very public. That allows participants to find spaces where they can meaningfully relate their interventions.

I wanted the project to feel grounded in the city’s fabric. I also really appreciate what Stefanie and Theo are doing with their work in relation to the water, while mine is more spread throughout the city. But in any case, I believe that the relationship to context is always the starting point of good design. Every successful spatial design searches for its meaning at the largest spatial scale, and anything we create should always respond to its surrounding environment.

© Samuel Causse

#10 Three things inspiring you at the moment?

I’m extremely inspired by idealistic philosophy, which is very specific but has a strong influence on my work. A few years ago, I made a book with the philosopher Bernardo Kastrup, who is like my intellectual hero. If I could have collaborated with anyone, it would have been him. After a few weeks of insisting online, he agreed to a two hour conversation, which led to the book. I am also part of a group where I meet with about fifty people every Tuesday evening to discuss idealism.

Idealism, in short, is the idea that reality is not fundamentally material but experiential. The smallest unit of reality is something mental or experiential, and what we perceive as matter is a representation of something mental. I read a lot of classical texts, especially Schopenhauer, Kant, and Hegel, but Schopenhauer in particular has always intrigued me. Bernardo Kastrup is a contemporary and very accessible thinker, and his ideas inspire much of my drawings, paintings, and the playful approach I try to bring to space.

Beyond philosophy, I am inspired by good urban spaces, places designed not to maximize profit but simply to be enjoyable to inhabit. In Copenhagen, I particularly liked Blågårds Plads, a small square with sculptures integrated into the walls, a place that combines social artwork with generous public space. I also love nature, botanical gardens, hiking in the mountains, and swimming in rivers. These experiences, being in water and feeling your body, are meditative and grounding.

Meditation itself is a practice I try to do every morning for twenty minutes. It can be boring sometimes, but it is rewarding, and over time it becomes a part of how I approach life and work. Drawing and painting are also meditative practices for me, ways to slow down, focus, and connect with the world. These influences, philosophy, urban space, nature, and meditation, come together to inform my work and how I engage with space.

© Samuel Causse

Links

Website: oliviergoethals.info

Instagram: @oliviergoethals.info

Photos by: © Samuel Causse, © Michiel De Cleene

Interview by Caroline Schulz