Common Accounts

Miles and Igor, please introduce yourself:

We are Common Accounts, an office for design inquiry led by Igor Bragado and Miles Gertler, supported by numerous collaborators and allies around the world, and based in Madrid and Toronto. We consult, we build, we write, we curate, always exploring the outskirts of architecture, where design intelligence is abundant, but under the radar. Much of our work has a focus on the body’s engagement with its environment as both subject and agent of design.

© Rainer Torrado

#1 Common Accounts has developed a distinct voice by working across architecture, media, and research. How would you describe your approach to practice today — and how has it evolved over time?

Our practice is driven by a desire to identify the cultural pulse and articulate the moment through design. We see architecture as a lens through which we can understand and engage with the lived environment (in other words, the world). We are not interested in architecture as a form of solidifying norms, but as a way of producing new questions and knowledge. Our work acknowledges that publics engage with architectural ideas through a variety of media, instruments, and situations. Our projects respond in turn, in those venues. We engage in different channels and formats of work (buildings, videos, publications, drawings, texts). Post-medium specificity is a posture that allows us to engage a range of attitudes, modes of storytelling, and creative outputs variously suited to each of the contexts we are working in.

#2 Your work often engages with topics that are culturally loaded or even taboo, such as death, intimacy, and digital life. What draws you to these themes, and how do you navigate the line between provocation and sensitivity?

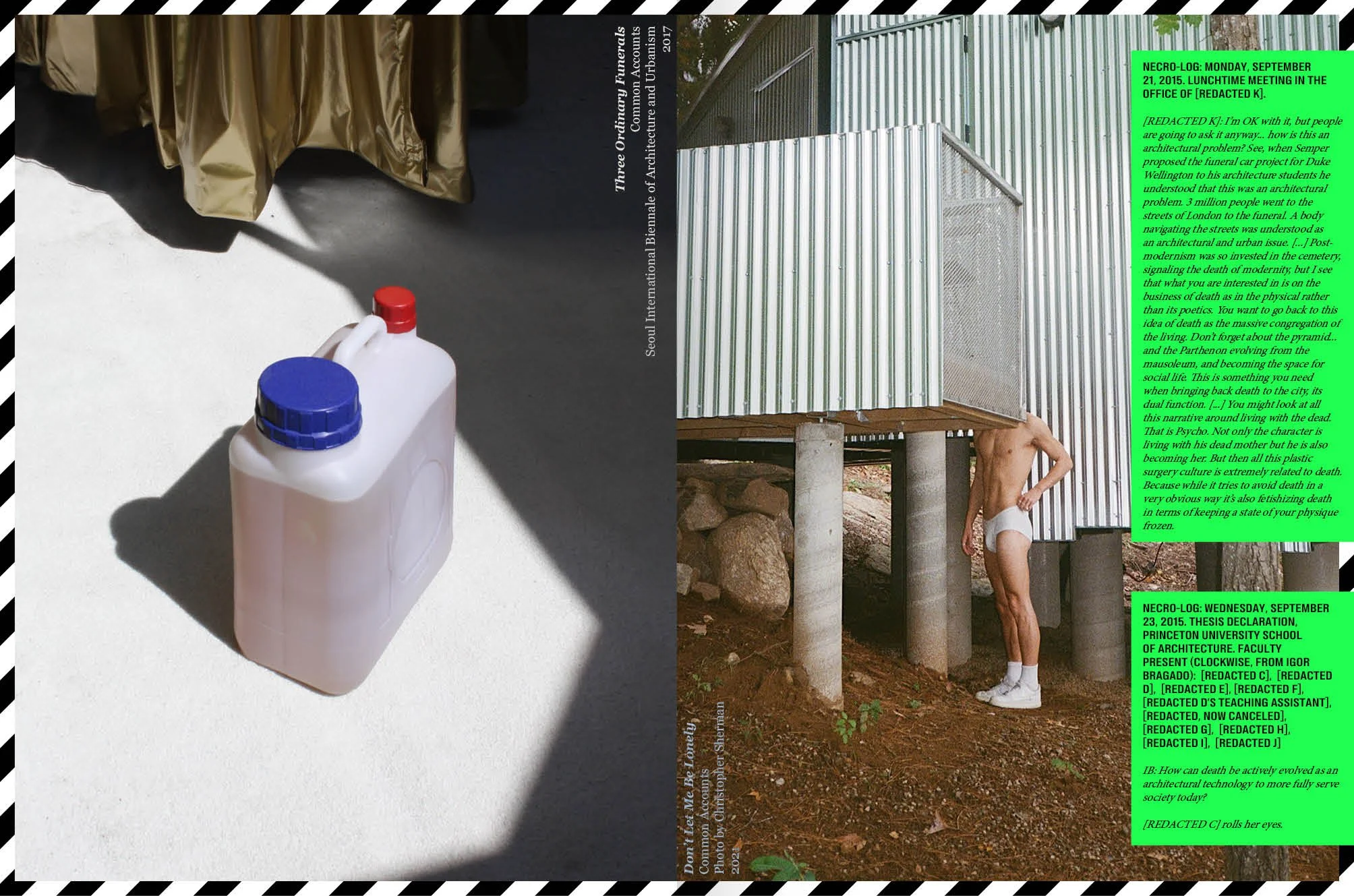

We are interested in cultural arenas where design action reflects radical changes in society but is almost entirely overlooked by architects and professional designers. Recently we’ve engaged with cultures like deathcare, fitness, and cosmetics. These are fields largely ignored by architects as sites of social, political or historical reflection—let alone action. Architecture seems to be mostly interested in houses, museums, luxury, and monographs. Often, these are locations where culture goes to fossilize: where established social dynamics are solidified, rather than invented. We see places like cemeteries, gyms, and make-up tutorial comment threads as key sites where people—mostly non-designers—are engaging with design in meaningful and transformative ways every day. We have much to learn from them. We are not interested in a model of architecture where the architect is an all-knowing technical figure who dictates what should or should not happen in a given space. We think that architecture ought to be, now more than ever, a practice of re-channeling, re-organizing, and re-distributing dynamics and design intelligence already at play. Architecture should be a practice of assembling techno-social situations to enhance the everyday, rather than a practice dedicated to formalizing capital.

#3 Have a Nice Day reimagines the sun as an artificial presence — ambient, programmable, and therapeutic. What drew you to this figure of the sun, and how did it become a lens through which to explore contemporary desires around care, control, and the future of the body?

Have a Nice Day began when Rafael Santianez and Scott Longfellow, curators at MUDAC in Lausanne, invited us to contribute to their show, Soleil-s, organized for the 2nd Solar Biennale. They had seen our prior exhibition, Clima Fitness, in Madrid, where we worked with curator Maite Borjabad to explore reciprocities between body and planet in the age of climate anxiety. We wanted to further this line of inquiry, considering affinities between scales both personal and planetary. With the sun, we turned our attention to Georges Bataille’s The Accursed Share (1949). He described the sun as a cosmic battery whose energy would fuel either libidinal or violent action in its recipients. We were interested in the sun’s psycho-social associations as both life source and hazard and developed Have a Nice Day with that duality in mind. This inquiry materialized a solar canopy: an interior sun apparatus suspended in the museum. Animated by motion sensors, the piece constitutes an artificial sun, inviting visitors to bathe under its warmth, sound, and light frequencies. The installation follows up on the notion of the sun as a battery, conscious that its rays are increasingly synthesized and replicated toward myriad purposes. Theorized among them: cellular rehabilitation, anti-aging, and enhanced fertility. As such, Have a Nice Day examines perceptions of the sun in relation to optimization, self-design, planetarity, danger, and the domestic realm, as the sun’s energy moves indoors.

© Common Accounts

#4 As an architectural installation, the project occupies the museum not only with structure, but with atmosphere. In what ways does Have a Nice Day reflect your interest in architecture as a medium for shaping sensory and temporal experience, rather than built form alone?

Have a Nice Day is a performance instrument for the cellular regeneration and degeneration of bodies, and as such, it develops our interest in fitness, meaning, the aptitude to resist and adapt to an environment. We are interested in the definition of architecture as an apparatus for the celebration, intensification, regeneration, preservation, and natural decay of bodies — human, botanical, animal, and planetary alike. The installation Have a Nice Day is suggestive in the way that it induces behaviors in passersby, and literally atmospheric in the way it influences climatic conditions in the gallery. It was important for us that its impact be sensible beyond merely the visual register: that the effects of the piece were embodied.

© Bruno Lança – ArtWorks

#5 The Death Report explores death as an ever-present condition rather than a distant event. How do you see architectural and spatial practices evolving to integrate death more openly and meaningfully into everyday environments, shaping how we live with presence and absence in daily life?

Our ongoing research into everyday, ordinary death—mostly focused on urban areas—shows us that it can be generative for the city and for society. This is something that has been known by many peoples in many places at many times: that death can be valuable as a social practice. That it has become remote from the everyday and consolidated as an industry is a result of modernisation and the desire to keep the city and home hygienic and sanitary. We see death and its spin-off activities (funeral, mourning, memorial) as pragmatic tools for city-building. But ultimately, our interest in death and fitness is a reflection on the discipline of architecture itself, as it has been to past thinkers who were similarly occupied with death and architecture. At the core, we are interested in reflecting on the composition and decomposition—indeed, the lifecycle, and survival—of the discipline.

© Common Accounts

#6 After eight years of research, what were the key moments or cultural impulses that sparked and sustained The Death Report project? Was there a specific event or idea that initially triggered your investigation into death as a design condition?

As a subject matter, it is a bottomless well. Death’s resonance and influence across architectural theories and histories, both distant and recent, is steadfast. Death—whether with reverence for it, or fear of it—remains active as a crucial, if subtle, constituent in the construction of daily urban life today. Our work, and every architectural work, we would argue, will always be about death as much as it is about life.

© Common Accounts

#7 How does your environment influence your work?

Deeply, in the sense that our common environment is the shared server infrastructure that stores everything we do. It is a pre-condition that stages the bridging of IRL and URL in all of our projects.

In terms of physical contexts, Madrid and Toronto are, broadly speaking, cities in which there is an established, conservative understanding of architecture as building. But look, there are two types of designers everywhere: enablers and agitators. We are obviously only interested in the latter, and Madrid is brewing a new generation of practitioners in that category, often interested in new-materialist thought, who read architecture as a social practice with the capacity to imagine more desirable political structures. When it comes to Toronto, we have less peers working through the same lens. But we are interested in the output of the city’s visual artists, filmmakers, musicians, chefs, and writers: those who remain and the many who have left. Toronto is a city abroad as much as a city at home. And while we will perhaps always feel like outliers there, we love it all the same.

#8 Three things that inspire you at the moment?

1. The generosity of our brilliant peers like Sina Sohrab, Andrea Muniáin, Charlie Robin Jones, Civil Architecture, Grandeza Studio, Chus Burés, and Space Popular; 2. The daily video-call discussions we have between Toronto and Madrid; 3. The things we read, watch and listen to.

#10 What do you currently read, watch, listen to?

Recently? The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills! Oklou! María Arnal! Joan Didion’s The White Album! Vilém Flusser’s Towards a Philosophy of Photography! Keller Easterling’s Subtraction! La Horde’s Age of Content! Michael Meredith’s Building With Writing Podcast! Casey MQ! Love Island!

© Bruno Lança – ArtWorks

Links

Instagram: @commonaccounts

Website: www.commonaccounts.online

Photo Credits: © Common Accounts, © Bruno Lança – ArtWorks, © Rainer Torrado

Interview by Caroline Steffen